The Incumbency Liability

Worldwide the electoral advantage associated with incumbency seems to be faltering, but was it ever worth that much?

Whether it’s due to a vibecessionary outlook on the economy, outrage towards foreign policy, or a perceived mishandling of border security, American voters have roundly rejected Kamala Harris. Harris could never detach herself from the legacy of Biden’s term and it appears that in their unprecedented swing to Trump, that the American electorate wanted to punish the incumbent Democrats.

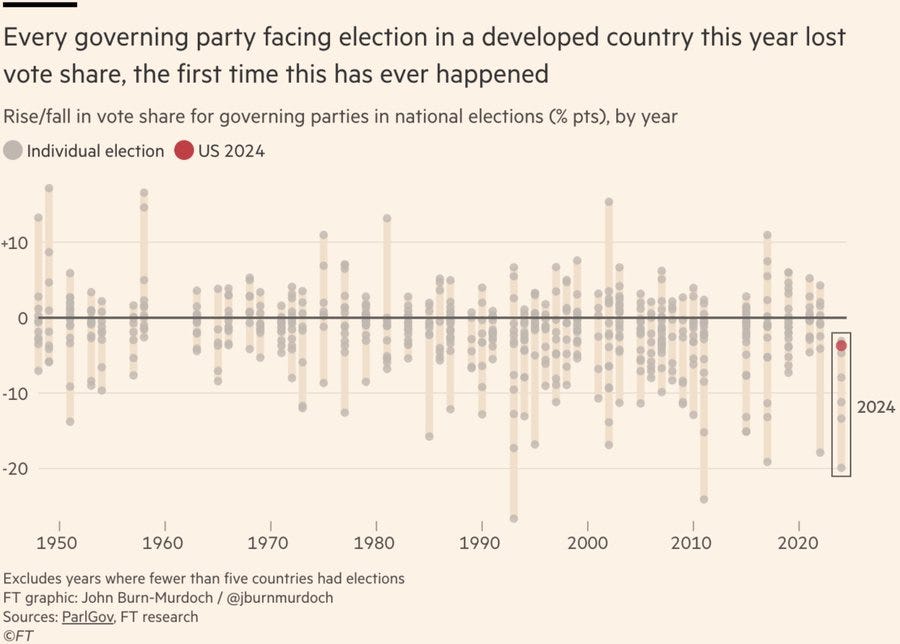

The US Presidential election naturally grabbed headlines more than any other, but 2024, the ‘year of elections’ will, by its close, have seen democratic elections in more than 50 countries, which contain over half the world’s population. There will have been more people voting than any other time in history. So far, many of them have voted against the party in charge, whoever it may be. In the UK, the Conservative Party suffered a profound defeat—despite being widely forecasted it, few seriously thought the party would receive its worst result in its modern history. More shockingly, the Botswana Democratic Party was voted out of power for the first time in 58 years. Elsewhere, Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party lost its parliamnetary majority and South America’s ANC received its worst election results since the end of apartheid. The far right in Europe won strong results in the European elections, matched by surges in support in the Netherlands and Austria. Against expectations, the success of the right-wing did not replicate itself in France’s snap Assembly elections, but Macron’s party still suffered with voters opting instead for a broad left coalition. Even in India, where Narendra Modi’s BJP had been dominant, the ruling party fell well short of its expectations and lost seats in the face of a more unified opposition coalition. In fact, according to a recent John Burn -Murdoch column in the FT, this is the first year in 120 years of recorded history that every incumbent party in a developed democracy has lost vote share.

The crises of the present decade seem to have driven global retaliation against many of the world’s democratic leaders. This wave seems uneprecedented and flies in the face of a well-established fact in political science: incumbents win. Of course, this is not all down to incumbency status itself—candidates will often win repeatedly because of their skill in campaigning, their proven record, or because the electorate that they serve stays largely the same in their beliefs and voting behaviour. However, even when these factors are controlled for it often appears that incumbents will win a higher vote share, and are more likely to win elections than challengers or candidates for an empty seat.

The first attempt to formally identify this phenomenon was Erikson (1972), which compared the change in electoral margins of first time incumbents compared to expected partisan swing in US congressional elections from 1952 to 1960. Methodologically, this paper now seems slightly crude, but later authors have often confirmed the presence (although perhaps have done the magnitude) of significant incumbency advantages.

This provides little solace to the ex-incumbent of 2024. However, the literature on incumbency advantage has become more contentious in recent years. In a year where voters have widely sought to punish whoever’s in charge, it may well be time to question what benefit, if any, incumbency has.

Identifying Incumbency Advantage

Incumbent electoral candidates in the USA experience incredible success in elections: House candidates are reelected at a rate of roughly 90% (Lee, 2008). Most of this is down to the candidates and electorates themselves: people rarely drastically change their voting behaviour and candidates are usually elected because their positions best represent those of the electorate. This is the main reason why safe Republican (or Democratic) districts stay that way.

However, there are a number of benefits incumbents enjoy that non-incumbents don’t that could bolster their election results. Some of these derive directly from holding office, such as access to fundraisers, franking privelege, and greater exposure to the electorate. Others are indirect, such as scaring off potential high-quality challengers (Levitt and Wolfram, 1997) or voters preferring candidates with greater seniority (McKelvey and Riezman, 1992). Incumbents may also benefit from having an individual record of positions distinct from their party’s protecting them from a shift in sentiment against their party (Pesowitz, 2019).

Evidence for incumbency effects largely rely on a quasi-experimental approach where the results of winners of close elections are compared to their losers. This was first implemented in Lee (2008), again, using data from US congressional elections.

This method, which users may recognise as regression discontinuity design (RDD) is intuitive and appealing. A lot of the issue with the identification of what degree of incumbents’ success is down purely to their being incumbents is that incumbents tend to succeed because they’re higher quality—in, at least, the sense that their skill at being elected is higher or they’re better matched to their electorates. However, it is pretty plain that the differences in quality between the loser and winner of an election with a 20 point margin of victory would be much higher than those of an election with a one point margin. The contestants in the latter election are actually likely to be more or less equal in their quality, with the result being determined by some quirk in the time of the election or minor shift in the characteristics of the electorate rather than the candidates themselves. If we, therefore, track the results in later elections of the candidates who just win to those who just lose these close elections, the degree to which barely-elected incumbents outperform barely-losing challengers makes a pretty convincing estimate of the effect that incumbency alone has on winning probability.

In fact, studying incumbency advantage in democratic elections is potentially the perfect playground for RDD. There’s no need to worry about getting around the application of inumbency being imperfectly applied to the winner of the election. Any candidate that has a positive margin of victory automatically receives the ‘treatment’ of incumbency. RDD also rests on the assumption that members of the treatment and control groups can’t directly choose their eventual treatment status. Of course, candidates can try what they might to influence the outcome of their election but they can’t, legally at least, control whether they win or their margin of victory. (We are very much assuming that these elections are free and fairly run. For an example of implementing RDD where this is not the case see Aksoy (2016).) Finally, as elections’ sole purpose is to grant incumbency to one candidate, nothing else that could change a candidate in a way that influences their future election result is discontinuoisly affected by the voting outcome. This sets elections apart from other areas where RDD could be applied. For example, policies that aim to help low-income households often have similar income thresholds to define who is eligible. This makes it problematic to isolate the effect of any of these programs individually, as testing the effect of eligibility for one will inevitably capture the effect of others.

Lee (2008) finds that between 1992-1998 incumbency status increases the likelihood of winning a seat in subsequent elections increases by 40 to 45 percentage points, with an average increase in the margin of victory of 8%. This is enormous, substantially higher than the estimated incumbency advanatge in Erikson (1971). Incumbent candidates in the senate also experience significant advantage. Cattaneo, Fransden and Titiunik (2015) find incumbency status yields a 7-9 percentage point advantage to election probability in these races. Across the literature, more of which will be explored later, RDD has become the canonical approach to identification.

The definition of incumbency advantage in Lee (2008) diverges somewhat from the traditional political science understanding of what incumbency advantage is. In Erikson (1971) and much of the subsequent pre-Lee literature, incumbency advantage is somewhat narrowly understood as the impact to the candidate of their own incumbency. Lee expands the unit of treatment to the party in power and any of their candidates in the same seat. These are comparable phenomena: if candidate quality does not influence voters then they’re identical. Erikson and Titiunik (2015) apply RDD to the level of inidvidual candidates and find similar impacts and generally argue that the methodology can be applied to personal incumbency advantage with some modifications to account for selection effects on quality of opposition candidates into races against incumbents.

While in theory the assumptions required for the application of RDD are very safe in the context of democratic elections, close elections may behave differently from typical elections in such a way to make them problematic. These are explored by Caughey and Sekhon (2011), who argue that the distribution of election results in close US House races suggest that sorting around the cutoff may violate the condition that candidates can’t manipulate their vote margin. The characteristics of candidates in barely-lost elections compared to barely-won elections differ in terms of party of incumbent, incumbents’ political experience and financial resources in ways that losers and winners in less contentious elections do not. In any given cycle, which elections are going to be close can more or less be identified before they take place. Parties will respond by directing financial resources to the races where they have the greatest marginal impact and electortes may be more mobilised, increasing turnout or raising the numbers voting strategically. This suggests that the comparison of bare winners and losers may be biased by some unobserved difference in quality, making RDD’s identification of incumbency advantage unreliable.

Even when controlling for the covariates that increase the election chances in close races Caughey and Sekhon (2011), still find evidence for incumbency advantage although of a much lesser magnitude. Evidence from less ‘professionalised’ races such as state assemblies and city councils also find substantial incumbency advantages (Trounstine, 2011; Uppal, 2010). Close races in these elections are, in theory, subject to less of the intense mobilisation that close House and Senate races might be.

Furthermore, Eggers et al. (2015) fail to replicate evidence for significant imbalance in any setting other than US House races, and highlight that even then the imbalance only affects elections within very narrow margins, where elections are lost and won by 0.5 percentage points. Polling isn’t accurate enough for candidates to be able to manipulate elections only within those very narrow margins in a way that close elections with higher margins do not. This, combined with the fact that post-war US elections is the only setting where there appears to be imbalance makes the assertion that it can only be explained by strategic manipulation less plasusible. Thus, the authors conclude, the lack of assumptions needed for RDD makes it a more reliable design for estimating incumbency advantages than other models.

The US vs Everywhere Else

In establishing the phenomenon of incumbent advantage focused on evidence from the US. This is chiefly because incumbency advantage does not replicate very well elsewhere. Alongside evidence from US House Elections, Eggers et al. (2015) present evidence from Canadian, New Zealand and British parliamentray, British local council, German Bundestag, French municipal and National Assembly elections, Australian House of Representative, Indian lower house, and Bavarian, Brazilian, and Mexican mayoral elections and find no incumbency advantage in any of them.

A number of papers do contradict this finding of a complete absence of incumbency advantage outside the US, particularly in developed democracies (Eggers and Spirling, 2014 in the UK; Horiuchi and Leigh, 2008 in Australia; Redmond and Regan, 2015 in Ireland; Kendall and Rekkas, 2012 in Canada; and Dano et al., 2022 in France). However, this is not universal. Evidence from Japan, for example, suggests that incumbents in the House of Representatives do not enjoy a substantial electoral advantage (Ariga et al., 2016).

There is growing literature suggesting that differences in the incumbency advantage are due to the characteristics of different political systems. Eggers and Spirling (2017) find evidence that stronger partisan preference in multi-party systems reduces the incumbency advantage as incumbents’ personal ‘valence’ becomes a less important factor in voters’ decision making. (Perhaps this suggests that US incumbency advantage could be decreasing with greater polarisation.) Other elements of multi-party systems could, however, strengthen the incumbency advanatage (Dano et al., 2022), although Ariga et al. (2016) suggests that multi-party systems offer greater opportunities for strategic coordination in opposition. Mixed-member district systems and proportional systems may weaken the incumbency advantage through greater intra-party competition (Ariga, 2015): non-incumbents in the same party as the incumbent will have comparative ease in competing away the incumbent’s voteshare, without the same financial and time obligations as the incumbent. Multi-member district incumbents also don’t have the same benefits of name recognition or be able to deter high-quality candidates as effectively.

The effect of incumbency in fragile democracies, where there is a high risk of election manipulation and interference, is very difficult to establish. There is very little literature in these settings and, due to the key assumption that vote share isn’t controlled by candidates, RDD would not yield reliable estimates. What evidence there is suggests an absence of real incumbency advantage. We know that representatives who are members of the party in charge do experience substantial advantages; however, this does not fit into the traditional understanding of incumbency advantage, with these advantages stemming from their party membership rather than their incumbency status.

In fact, outside of the US, there is a great deal of evidence that voters in many contexts have a tendency to punish incumbents. Incumbency disadvantage is observed in Indian state legislatures and National elections (Linden, 2004; Uppal, 2009), Central and Eastern Europe (Roberts, 2008), and Brazilian mayoral elections (DeMagalhaes, 2015; Klasnja and Titiunik, 2017, who also find disadvantage elsewhere in Latin America). This suggests that the global backlash against incumbents observed in 2024 is not a new phenomenon for much of the world.

Disadvantage appears more present in younger democracies. Roberts (2008) terms incumbents’ disadvantage in Central and Eastern Europe ‘hyperaccountability’—even under relatively favourable economic conditions, incumbents perform poorly, with poor economic conditions resulting in much larger losses. Thus incumbents are punished for less Myerson (2006) presents incumbency disadvantage as a pessimistic equibrium in democracies in transition from authoritarianism—electorates expect low returns from democracy and corrupt behavour. Therefore, incumbents are repeatedly not re-elected and have no incentive to refrain from corrupt behavior reinforcing this state of affairs. Klasjna (2016) also attributes incumbency advantage to corruption—with expectations of corruption, ‘good’ politicians can’t as effectively signal their quality, reducing incumbent quality and increasing office-holder turnover.

The Boot

Down ballot, Democrats performed better than Kamala Harris, even if at this stage they have lost the senate and seem on track to lose the House. It is in these races where the evidence for incumbency advantage exists, and not the Presidential election. One couldn’t conduct a convincing study on incumbency advantage in Presidential elections—there aren’t enough of them. I doubt that Presidents do receive any real incumbency advantage. Voters receive more information, have stronger partisan preferences, and are more mobilised for these than any other races. In general, they are subject to the same conditions that led Caughey and Sekhon (2011) to question its presence in House races—they are the most ‘professionalised’ elections in the world, with both of the main candidates having the backing of substantial institutional power.

Let’s return to the FT column I referenced in the introduction. The distribution of incumbent party results on the far right of the graph shows the Democrats faring better than almost all other incumbent parties in 2024.

US voters, it may appear, remain among the less retaliatory towards their incumbents. This is not solely attributable to any incumbency advantage; if we are to understand the backlash as a response to rising inflation or increased global migration, as Burn-Murdoch suggests, then one must take into account that the American economy has, in terms of headline measure, performed much better than other developed economies.

Strong incumbency advantages aren’t necessarily desirable in so far as they prevent good candidates from running and winning. However, from the recent it is clear that any positive incumbency effects, however large, can never be expected to survive broad-based dissatisfaction with economic conditions. One can’t read onto the 2024 election results an attack on Democrats simply because it is they who are in charge. But one could become wary of voters becoming retaliatory towards incumbents—lack of faith in incumbents’ integrity and increasing partisanship could be destabilising. The uncertainity surrounding Trump’s election shows little promise of slowing these trends down.

References

Aksoy, O. (2016) ’Regression Discontinuity diagnostics reveal statistical anomalies in Turkish elections’, Electoral Studies, 44, pp. 284-292.

Ariga, K. (2015). Incumbency disadvantage under electoral rules with intraparty competition: Evidence from Japan. The Journal of Politics, 77(3), 874-887.

Ariga, K., Horiuchi, Y., Mansilla, R., & Umeda, M. (2016). No sorting, no advantage: Regression discontinuity estimates of incumbency advantage in Japan. Electoral Studies, 43, 21-31.

Cattaneo, M. D., Frandsen, B. R., & Titiunik. (2015). Randomization inference in the regression discontinuity design: an application to party advantages in the U.S. senate. Journal of Causal Inference, 3(1), 1–24

Caughey, D., & Sekhon, J. S. (2011). Elections and the regression discontinuity design: Lessons from close US house races, 1942–2008. Political Analysis, 19(4), 385-408.

Dano, K., Ferlenga, F., Galasso, V., Le Pennec, C., Pons, V. and National Bureau of Economic, R. (2022) Coordination and incumbency advantage in multi-party systems : evidence from French elections Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working paper series no. w30541. Available at: https://www.nber.org/papers/w30541. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.3386/w30541.

De Magalhães, L. (2015) ’Incumbency Effects in a Comparative Perspective: Evidence from Brazilian Mayoral Elections’, Political Analysis, 23(1), pp. 113-126.

Eggers, A. C., Fowler, A., Hainmueller, J., Hall, A. B., & Snyder Jr, J. M. (2015). On the validity of the regression discontinuity design for estimating electoral effects: New evidence from over 40,000 close races. American Journal of Political Science, 59(1), 259-274.

Eggers, A. C. and Spirling, A. (2017) ’Incumbency Effects and the Strength of Party Preferences: Evidence from Multiparty Elections in the United Kingdom’, The Journal of Politics, 79(3), pp. 903- 920.

Erikson, R. S. (1971). The advantage of incumbency in congressional elections. Polity, 3(3), 395–405. Gelman and King (1990) Estimating Incumbency Advantage without Bias.

Erikson, R. S., & Titiunik, R. (2015). Using regression discontinuity to uncover the personal incumbency advantage. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 10(1), 101-119.

Horiuchi, Y., & Leigh, A. (2009). Estimating incumbency advantage: Evidence from multiple natural experiments. Working Paper.

Kendall, C., & Rekkas, M. (2012). Incumbency advantages in the Canadian Parliament. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d'économique, 45(4), 1560-1585.

Klašnja, M. (2016). Increasing rents and incumbency disadvantage. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 28(2), 225-265.

Klašnja, M. and Titiunik, R. (2017) ’The Incumbency Curse: Weak Parties, Term Limits, and Unfulfilled Accountability’, American Political Science Review, 111(1), pp. 129-148.

Lee, D. S. (2008) ’Randomized experiments from non-random selection in U.S. House elections’, Journal of Econometrics, 142(2), pp. 675-697.

Levitt, S. D. and Wolfram, C. D. (1997) ’Decomposing the Sources of Incumbency Advantage in the U. S. House’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 22(1), pp. 45-60.

Linden, L. (2004) ’Are Incumbents Really Advantaged? The Preference for Non-Incumbents in Indian National Elections’. Thesis. https://casi.sas.upenn.edu/sites/default/files/iit/Incumbency%20Disad.pdf

McKelvey, R. D. and Riezman, R. (1992) ’Seniority in Legislatures’, The American Political Science Review, 86(4), pp. 951-965.

Myerson, R. (2006). Federalism and incentives for success in democracy. Working Paper. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9940s9bv

Peskowitz, Z. (2019) ’Ideological Signaling and Incumbency Advantage’, British Journal of Political Science, 49(2), pp. 467-490.

Roberts, A. (2008) ’Hyperaccountability: Economic voting in Central and Eastern Europe’, Electoral Studies, 27(3), pp. 533-546.

Redmond, P., & Regan, J. (2015). Incumbency advantage in a proportional electoral system: A regression discontinuity analysis of Irish elections. European Journal of Political Economy, 38, 244-256.

Uppal, Y. (2009) ’The disadvantaged incumbents: estimating incumbency effects in Indian state legislatures’, Public Choice, 138(1-2), pp. 9-27.

Uppal, Y. (2010). Estimating Incumbency Effects in US State Legislatures: A Quasi‐Experimental Study. Economics & Politics, 22(2), 180-199.